More than a dozen 2020 U.S. House and Senate candidates have engaged with the collection of conspiracy theories known as QAnon. At least two of those candidates won their races and will be heading to Congress in 2021.

Here are five facts about how much Americans have heard about the QAnon conspiracy theories and their views about them, based on Pew Research Center surveys and analysis.

To understand how much exposure Americans have to QAnon and the conspiracy theories associated with it, we surveyed 9,220 U.S. adults between Aug. 31 and Sept. 7, 2020, to first determine how much respondents had heard of QAnon and then asked them to write in their own words how they would describe the group. Everyone who took part is a member of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

Responses to the open-ended question were analyzed using a combination of machine keyword analysis and human coding.

For details on the YouTube analysis, see the methodology. All videos published in September 2020 by the 11 channels that mentioned QAnon in at least 10% of their videos in December 2019 were coded for mentions of QAnon.

Here is the methodology for this report.

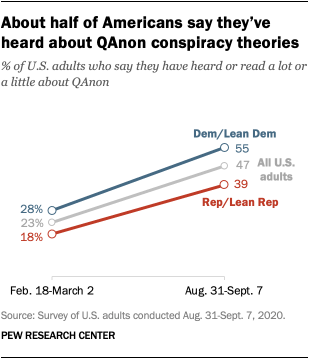

Americans’ awareness of the conspiracy theories called QAnon increased dramatically from early to late 2020. In a Feb. 18-March 2 survey, about a quarter (23%) of U.S. adults said they had heard “a lot” or “a little” about QAnon. By September, that number had increased to 47%. At the same time, though, very few Americans have heard a lot about it: 9% as of September, up from 3% in February.

Knowledge of QAnon grew on both sides of the political aisle, though Democrats’ awareness continues to outpace that of Republicans. As of September, more than half (55%) of Democrats and those who lean Democratic say they have heard at least a little about the conspiracy theories, compared with 39% of Republicans.

The same U.S. adults were sampled for the March survey and September survey. This raises the possibility that some of the increase in QAnon awareness is attributable to re-asking the same people.

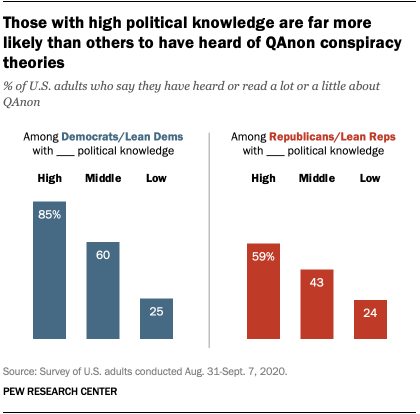

Americans with high political knowledge are more likely than others to have heard of the conspiracy theories. Within both parties, political knowledge correlates closely with awareness of these theories.

Among Democrats, those with high political knowledge are more than three times as likely to say they have heard about QAnon (85%) as those with low political knowledge (25%). And though fewer Republicans overall have heard of QAnon, those with high political knowledge are more than twice as likely (59%) as those with low political knowledge (24%) to have heard at least a little about QAnon. (You can find more details of the political knowledge index here.)

High or low political knowledge is a stronger factor in awareness of the conspiracy theories than differences in ideology within each party. The differences seen between Democrats with high and low knowledge are much larger than the differences seen between liberal Democrats and conservative or moderate Democrats, and the same is true among Republicans.

The majority of Americans who have heard of QAnon think it’s a bad thing for the country. Among those who have heard of the conspiracy theories, 57% say QAnon is a “very bad” thing for the country. Another 17% say it is “somewhat bad.” That compares with 20% who say it is a somewhat or very good thing, while 6% did not answer.

Democrats who have heard of QAnon are more likely than their Republican counterparts to say it’s bad for the country. Almost eight-in-ten Democrats who have heard of QAnon (77%) say it is a “very bad” thing for the country, and another 13% say it is a somewhat bad thing. On the other hand, only about a quarter of Republicans who have heard of QAnon (26%) feel it is very bad for the country, while 24% say it is somewhat bad. Indeed, roughly four-in-ten Republicans who have heard of QAnon (41%) say it is a good thing for the country (32% somewhat good and 9% very good).

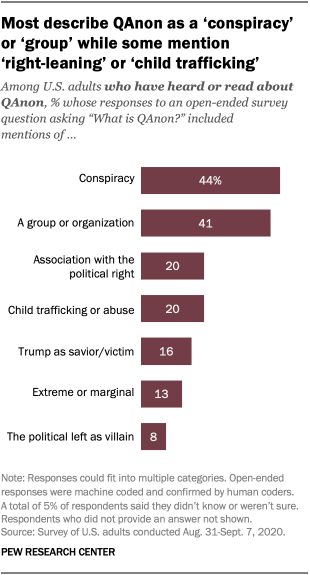

When asked to describe QAnon, people most often mentioned that it was a group of some kind (41%) or a conspiracy group or theory (44%). When Americans who said they had heard at least a little about QAnon were asked to write in their own words what they thought it was, they were most likely to describe it as a group of some kind or include a more specific description of it as a conspiracy group or theory.

Far fewer wrote in other kinds of descriptions. Two-in-ten mentioned that it is a right-wing group or theory (20%) or that it is a theory about child abuse or trafficking (20%). Another 16% connected it directly to President Donald Trump, either by saying that Trump supports the group or that the group views him as a hero, savior or victim. (Responses could fit into more than one of these categories.)

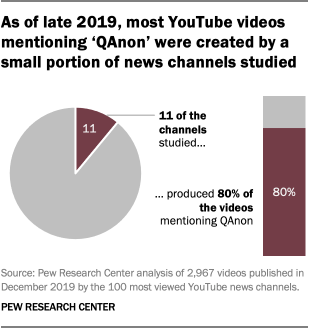

A separate content study of YouTube by the Center found that in December 2019, mentions of “QAnon” were concentrated in a very small number of the most viewed news channels. Overall, 5% of videos published by the 100 most viewed YouTube news channels at the time of the study included the word “QAnon.” The vast majority of those mentions came from just a handful of YouTube news channels: 11 of these channels studied produced 80% of the videos mentioning QAnon.

In a subsequent content analysis conducted in September 2020, eight of these 11 YouTube news channels were still producing videos that mentioned QAnon. What’s more, four of them mentioned QAnon in half or more of the videos they published that month.

Some of these channels clearly advertised their orientation around these conspiracy theories, including one that put the word “QAnon” in the thumbnail of all of its videos. Other channels were more subtle in their mentions, using euphemisms such as “our favorite anon.”

Several of the 11 channels were terminated by YouTube in October, including some channels that mentioned QAnon the most in September 2020.

Note: Here is the methodology for this report.